In 2016, the Colombian government came to a peace agreement with the FARC rebels, ending more than five decades of civil war. ‘I’m all but in favour of the FARC, but one of the positive terms they wanted to stick to in the agreement was the countrywide registration of land rights,’ says Javier Morales, one of the ITC researchers involved in the project. ‘This part of the treaty was so well-put together that the government couldn’t refuse. Since then, the government has to map and register all of the countries’ parcels within seven years.’

Too slow, too expensive, too complex

First, the Colombian government made an estimation of how many properties there are still left to register. The urban areas were mostly covered in that regard. But it’s a whole different matter for the rural areas. According to Morales, the Colombian government has about forty percent of the rural areas registered – of which forty percent contains outdated information. ‘The government estimated that they still had about five million parcels left to register – which is a fairly reasonable amount left to cover. However, there is a multitude of problems with the current way the government handles this: the pace is too slow, the costs are too high and the procedures are too complex.’

'A bank only lends money if you have a title'

When Morales compares the Colombian procedure to the Dutch, the situation becomes even more poignant. ‘In the Netherlands, you go to the notary – who makes sure the Kadaster takes care of mapping and measuring parcels and their legal status. In Colombia, you have to go to three separate institutions yourself.’ Another issue is the standard procedure of measuring, says Morales. ‘The combined costs of equipment, methodology and human resources: about 500 dollars. Most people don’t have that kind of money. Even worse, some people’s property aren’t even worth that much.’

To add insult to injury: by Morales’ calculations, if the Colombian government institutions would measure and register five million parcels with their current methods, it would literally take centuries to do so. ‘But when they started measuring, early 2018, they realised that it’s not five million parcels that have to be measured, but twelve million. The problem turned out to be much bigger.’ Moreover, Morales stresses the importance of proper land rights. ‘Especially farmers want to develop their land. For that, they need money. And a bank only lends money if you have a title.’

Fit for purpose

Enter the Dutch Kadaster and ITC. ‘We wanted to tackle the three expensive and time-consuming factors all at once,’ says Morales. ‘So we tried to reduce the costs of equipment, methodology and human resources, while still abiding to the LADM, the international standard of land administration. That was our baseline.’

The researchers came up with a fit-for-purpose (FFP) application. ‘We settled for a land measuring device that was able to deliver accuracy between 10 centimetres and a meter, depending on varying circumstances like hillsides and foliage,’ explains the ITC researcher. ‘The idea was to combine that with a simple application in which we registered the personal information of the owner or tenant, so we had both the land mapped and the person who it belonged to. After several tests, where – admittedly – a lot of things went wrong, we decided which app we wanted to use.’

'Wherever there is a border, there is bound to be conflict'

The human aspect

Understanding the technology is one thing. But then there’s the human aspect. The pilot took place in two small rural villages: Los Mandarinos and Termales. ‘We started by informing the local communities. It came down to expectation management: maybe the people could get land titles and maybe not. We had to be very clear about our tests and the way it would work.’

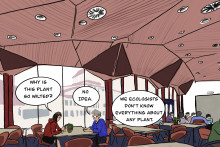

Another part of the human aspect was the use of local youngsters. ‘They’re way more proficient with technology than the local farmers,’ says Morales. ‘Besides, people can get sensitive about their possessions. Wherever there is a border, there is bound to be conflict. So we wanted to have a neutral party involved. The measurements are taken by the owner, who carries the GPS unit, and the youngster - we call them grassroot surveyors - who uses the app. The idea is that the farmer, who knows the property well, points out his or her own boundary to avoid misunderstandings and not have the people involved measuring their land themselves, to avoid discrepancies. We assigned one FFP expert per community and trained local youngsters in the procedure and how to use the app. They accompanied the farmers to measure their own parcels. And of course, the people had to provide evidence that there is a relationship between them and the land. In the end, it comes down to trust. It really helps if they’re there to see it with their own eyes.’

After the measuring, the locals gather again to check the collected data on a map. It’s still possible that there are discrepanciess amongst neighbours, says Morales. ‘Since our measuring unit isn’t accurate to a centimetre, it can happen that some areas overlap. In that case, the local FFP expert and the farmers discuss the facts together to solve the problem.’ The ITC researcher says trust again plays a big role in the following step. ‘If someone agrees with the measurements, they write down their signature. In a way, the proof by means of accuracy becomes secondary you could argue that the signatures of two neighbours adds more reliability and value than the decision of an external party as to who get the rights to a piece of land. Of course, if you sign, you agree that the government uses the data to give you a title.’

Mark Rutte

The results of the FFP project by ITC and the Kadaster speak for themselves: in four days in Termales, 75 parcels were measured. In Los Mandarinos, it took three days to measure 55 parcels. Only one conflict did not get resolved. ‘I believe we have demonstrated that measuring land can be done fast, cheaper and can result in land titles,’ says Morales. ‘Instead of 500 dollars, our method costs about 25 dollars.’

Still, the government institutions aren’t full convinced about the FFP method. ‘Apparently it’s difficult for some civil servants to understand that they are there to help the citizens. But they also know that fast and effective land administration is essential for the implementation of the peace agreements, and to maintain public confidence in the peace process. They’re finally starting to turn around and we hope the government will pass a law soon that allows the local municipalities in charge of registering land.’

'Mark Rutte could have posed in front of a government building, but he actually went to Los Mandarinos himself to hand out the first land deeds'

Aiding the ITC researchers and the Kadaster are efforts by the Dutch ambassador in Colombia and a visit from Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte. ‘The Dutch embassy keeps informing the Colombian government that our method is working,’ says Morales, who’s even more enthusiastic about the efforts by Mark Rutte. ‘He went to Colombia last year. He could have posed in front of a government building, but he actually went to Los Mandarinos himself to hand out the first land deeds to the local community, based on our method. That helped us a lot in being taken seriously.’ He jokingly adds: ‘The only people not happy with him were the security personnel, who had to escort 25 vehicles over a single lane dirt road.’

‘We can always educate people at local universities on the principles behind FFP, even if the Colombian government were not to support our method,’ says Morales. ‘At ITC, we’re not necessarily interested in property, but in developing knowledge that helps people by directly addressing their needs. So if you would ask what’s next for us in Colombia, I would say helping the farmers be more productive on choosing which crops to grow and where. I’m originally from Colombia myself. What better way than to use my own skills that others can benefit from?’