The Australian artist will discuss his vision on merging humans and technology, something he has first-hand experience with. We’ve met up with Stelarc in Tetem, where you can find his latest installation StickMan.

Stelarc in a nutshell

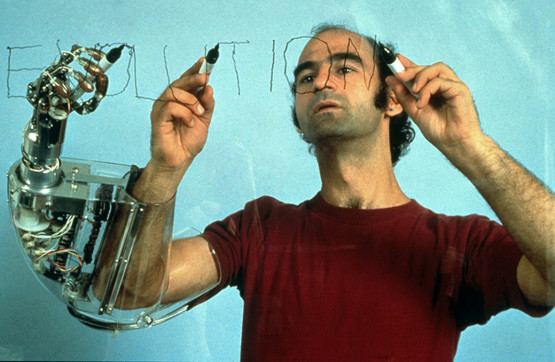

Stelarc is a performance artist whose projects mainly focus on extending the capabilities of the human body. In his performances he often uses prosthetics, robotics, suspension, biotechnology and the internet. Some of his most famous projects include The Third Hand, a six-legged exoskeleton and the extra ear on his left arm.

'The Third Hand' Photographer: Keisuke Oki; 'Six legged Exoskeleton' Photographer: Igor Skafar; 'Propel' Photographer: Steven Aaron Hughes

First I must ask, is your third ear already fully functional? I know the plan is to allow people to log on and listen through your ear. Is anyone listening right now?

‘No, not yet. It’s been a very long project that began in 1996. It took ten years to find funding and surgeons to construct and implant the ear into my arm. This June, we will finally start making a soft ear lobe grown with my stem cells. Afterwards we will implant a Wi-Fi chip and a microphone. It will hopefully be fully completed in spring 2019, after which anyone in the world will be able to listen through my ear. It will be used by other people, not me. I already have two good ears.’

What brought you to Twente?

‘It’s a very special trip, I’m not going anywhere else in Europe. I’m here to present my latest project StickMan which will be exhibited in Tetem for a few months. It’s a full-body exoskeleton that algorithmically actuates the artist. It’s designed for the artist to perform with it. Especially for Tetem, we developed a physical interface that I call a “mini StickMan” and that allows the audience to control the movement of the exoskeleton. I will have a short performance tonight and a five hours long performance on Sunday, when visitors can come and just watch or interact.’

What will you talk about during your presentation at the UT tomorrow?

‘It’s an opportunity for me to talk about all of my work, from early body suspensions to the more recent robotic performances. And to discuss implications of these technologies. I’m not only interested in performances, but also in what they generate in terms of ideas.’

Your artistic work has generally focused on enhancing the human body. Why?

‘I don’t like to use the word “enhancing” anymore. I like to speak of experimenting with alternate anatomical architectures. It’s about interrogating the human body, exploring its limitations. I began focusing on this type of performances when I discovered I was a bad painter at art school. That is true. (laughs) But I’ve always been interested in the evolutionary development of the human body. It’s very unique. Other living things see and interact with the world very differently, so I’ve had interest in the biological architecture of the body, which is increasingly inadequate in our world. I’ve wanted to explore how we can augment the body, increase its performance. Why can’t we see in X-ray or infrared spectrum? We evolved as proximal creatures. We perform as individual bodies in proximity to other people. However, technology enables us to perform beyond the local space we inhabit, beyond the boundaries of our skin.’

Ear On Arm Suspension. Photographer: Polixeni Papapetrou

Peter-Paul Verbeek, one of the UT professors with whom you will have a discussion tomorrow, once said that ‘Humans are artificial by nature.’ Would you agree with that?

‘Yes, I would. The human body has always been a prosthetic body. To be human means to construct artefacts, to construct culture, language, to be curious and attempt to extend our perception of the world beyond our normal biological operation. We have a certain nostalgia for “human”, but being human has never been only about having a body. To be human means to have technology. Technology creates humanity.’

'Technology creates humanity.'

Your tomorrow’s talk is titled ‘Merging man with technology’. How far do you think this ‘merging’ will go?

‘I’m not interested in sci-fi speculations of the future. As an artist, you want your idea to be meaningful, you need to actualize it. By doing that, you create something that didn’t exist before. You are turning your present into future. Future isn’t something that exists somewhere without you, you are constantly constructing it. What artists do best is engineering contestable futures. Showing some of the possibilities, alternate unexpected scenarios. But we make gestures, not scientific facts. To simplify it: science is about information, art is about affect.’

You are also an honorary professor at several universities, right?

‘Yes, but I’ve always said I’m only an artist. There has been this movement of meshing art and science together. There is nothing inherently wrong with that, except we sort of misunderstand what research means. You don’t want artists to do bad research and scientists to make bad art. You don’t need to mix methodologies. I’m a Distinguished Research Fellow in the School of Media, Creative Arts and Social Inquiry at the Curtin University in Perth, but I’m not an academic. Doing full-time research in my case means being a full-time artist.’

What projects are you working on right now?

‘StickMan only just finished, but no project is ever really finished. “The Ear on Arm” is of course an ongoing project. When fully realized, it will be a kind of “Internet Organ”. Technology is the external organ of the body. Our body is inadequate and so we are developing additional organs. Think of transplants: we are even able to give face transplants, we can stitch a new arm onto an amputee, we might soon be able to 3D print organs. The body you were born with is not necessarily the body you will die with. As I say, we live in the time of circulating flesh. The human body is a chimera of meat, metal and code.’

Stelarc in Twente

If you’d like to see Stelarc ‘in action’, you can join his talk in DesignLab tomorrow at 16:00 or visit Tetem (Enschede), where his installation StickMan will be exhibited until the 19th of August. The performance of StickMan will take place tonight and on Sunday, 27th of May.