‘It may seem like a smooth upward curve’, says Jai Prakash about his scientific career, ‘but each of my successes is accompanied by a thousand failures. Only no one sees that.’

Between Lab and Life

What if you get rejected for that prestigious grant yet again? If your set-up breaks down or if there is a dispute in the workplace? A scientist’s career is no bed of roses; it is a journey of ups and downs, trial and error. Science journalist Enith Vlooswijk talks to five UT scientists about the difficult path to success. This is episode 1 of Between Lab and Life: Jai Prakash.

Indeed, the CV on the personal web page of Prakash (46), professor of engineered therapeutics, looks like a resounding success story. He completed his PhD in the field of targeted drug delivery cum laude in Groningen, after which several international research institutions tried to rope him in. He decided to join the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, but in 2012, the University of Twente lured him back to the Netherlands to set up his own research laboratory within a tenure track. He and his team have since been developing new therapies to treat cancer, which he tests using three-dimensional tumour models. He founded the spin-off company ScarTec Therapeutics, initiated international collaborations and the list goes on. But these successes are just a very tiny fraction of his reality.

What the page does not show is that Prakash, like most of his colleagues, spends over seventy per cent of his time trying to scrape together funds for research and that nine out of ten grant applications end in disappointment. By now he is used to it, but that was not yet so when he missed out twice on the coveted Vici grant: the NWO grant for excellent senior researchers.

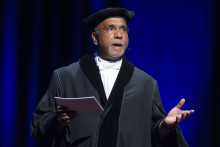

(Text continues below photo.)

A Vici application consists of four rounds. First, the applicant writes a ‘pre-proposal’ with a rough outline of the idea. If this gets approved, it is time for the ‘full proposal’ with fleshed-out ideas. The applicant then receives feedback from reviewers, to which they can respond. If these three rounds proceed smoothly, the applicant attends an interview with a panel of experienced scientists. ‘That interview is no longer about science’, says Prakash. ‘Most panels are too broad and don’t have a clear understanding of what you’re talking about. I myself have been on panels for two applications for mathematical research and couldn't get past the abstract.’

If the decisive interview is not about the content, then what is it about? ‘It’s about you. About the feeling. How do you talk? Are you an active speaker, do you speak slowly? What is your demeanour like, how do you come across, are you charismatic? Everything matters, except for science.’

Prakash was eliminated in that fourth round. What did not help, according to him, was that he was thrown into the Twente research pool as a newcomer. He could not draw on the existing reputation of a research group because he had to start building it from scratch. ‘It takes a lot of time to establish contacts and become embedded in the research world. I missed that sense of embeddedness in the beginning.’

In the three years after his arrival in the Netherlands, Prakash worked on building his research group. It was a daunting task: every single pipette, every single paper towel for the lab still had to be procured. ‘We had to build everything from the ground up, even getting simple techniques to work was difficult. It was a great learning experience, but bad for my career, because it left a gap in my publication record. As a scientist, you’re not judged on setting up a lab but on your output, aka your publications.’

Perhaps that also played a role in the outcome of the first Vici application, which, like the second attempt, ended with a let-down in the final round. A major setback, as any Dutch researcher who wants to reach the top is well aware. ‘If you’re awarded the right grants early on in your career, it’s easier for you to get grants in the future’, says Prakash. ‘That’s called the Matthews effect: early successes increase the chances of future success. The panels see that and think: that guy has won a lot of grants, he must be good!’

Still, he does not blame the panels, Prakash stresses. ‘No one is happy with the system. We’re all trapped in it and no one knows a way out.’

A bitter pill, but no reason to throw in the towel. Now, almost ten years later, the professor even sees advantages to missing out on the Vici grant. ‘The first time you receive such a rejection, it’s like plummeting down from the tenth floor. The second time you already know where to land and try to land on an air cushion, making you jump even higher than before. I knew I couldn’t apply for a Vici again, so I tried even harder to push my research forward so that I could achieve more and perform better. Science is like top-level sports. Top athletes train, fail, train more and reach higher levels all the time. It’s a fight. The day I give up fighting is the day I quit science.’

Interested?

Enith is still on the lookout for UT researchers to interview about ‘their difficult times’ in science. Are you interested? Then please send an email to [email protected]