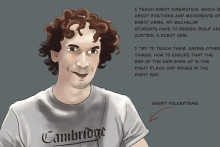

The ink on his master's degree had barely had time to dry before Robin de Graaf began teaching his first course as a doctoral candidate. A few short months before, he had been sitting alongside these people as a student. Now, he was the one doing most of the talking. The new relationship between him as a lecturer and his students took some getting used to.

Nevertheless, he soon caught the teaching bug. Over the past twenty years, he has taught numerous students as a university lecturer with the Civil Engineering programme. De Graaf quickly discovered that he loves to try new things. It energises him. He switched from teaching the process management course to systems engineering and then to the value management course. Provide PDEng education on the side? Yes, please! When the Twente Education Model was first introduced, he did not resist the change. Instead, he stood at the head of the crowd, eager to try something new. Above all, he was curious to see the effects of such a radical new approach to education.

Innovation is a means to an end, not the end itself. Whether he's dealing with a major change or a minor one, De Graaf is all about quality: plan, do, check and then do again. The students come first, they have to learn something. That cannot be expressed with just a numerical grade. The process is at least as important as the result.

That is why the Civil Engineering teacher is going all-in on Challenge Based Learning. De Graaf is convinced of its importance and necessity. After all, when a freshly graduated UT alumnus enters the professional field today, they are expected to possess different skills than would have been the case twenty years ago. One of these requisite 21st century skills, De Graaf says, has to do with not being stuck in your own field, but learning to speak other people's language. Another revolves around being adequately equipped to work on issues that cannot be resolved overnight, like the energy transition or the climate crisis.

Challenge Based Learning also gives De Graaf an opportunity to bring such complex societal issues into the classroom. The reverse is also true: a municipality or the world of business can benefit from the fresh perspective that students have on cases taken from real life. That is precisely what sets Challenge Based Learning apart from classical project-based education. Its strength lies in the interaction between the student and society, De Graaf says.

He strives to build that bridge in his own education as well. For one course, in collaboration with the Municipality of Enschede and Sportaal, his students focus on the redevelopment of the Diekman area. Freedom of choice is an important concern: whoever has affinity with the optimal layout of the parking spaces is made responsible for that part of the project. Someone else can then focus on the sports facilities or the traffic flows. After all, students learn better when they are excited about what they are doing. If you do not enjoy the process, you will learn very little along the way. However, he is quick to add, every student has to master the basics. A student of civil engineering who cannot design an overpass will look bad.

De Graaf is not just a proponent of Challenge Based Learning. Last spring, he was also made one of the UT's seven Teaching & Learning Fellows. The main goal is to determine how and where Challenge Based Learning can be implemented at the UT. That does not happen overnight; they work evidence-based and look at what has proven itself and build on it. After all, there is a reason why Challenge Based Learning is such an important aspect of the UT's new vision Shaping 2030.

As a Fellow, De Graaf can clear a metaphorical path for others interested. That is not a question of coercion or pressure - on the contrary. Who chooses to walk down that path depends on the individual lecturer and the contents of the course. Like others before it, De Graaf says, this educational innovation is a means to an end, not an end in and of itself. You can choose to follow in his footsteps if doing so will enrich your educational palette and allow students to learn more effectively. That was the essence twenty years ago and it still is today.