Current screening techniques for breast cancer result in 10 to 20 per cent of patients wrongly being sent home with good news, says UT researcher Foad Sojoodi Farimani. He is one of the project leaders of the European research project MURAB, which stands for MRI and Ultrasound Robotic Assisted Biopsy.

Farimani’s goal is to significantly reduce this percentage of false negatives. ‘If a mammography shows a suspicious image then we need to take a small piece of tissue for lab examination. But it’s difficult to determine precisely where the biopsy should be carried out. As a result we overlook too many patients who do indeed have a problem. That’s an issue we hope to solve.’

Expensive MRI and cheap ultrasound

A biopsy in the MRI scanner could present a solution, explains Farimani. ‘MRI does not generate any radiation, has no side effects, and you can determine very precisely where you should do your biopsy. But it’s very expensive and it takes about 45 to 60 minutes a patient. Even wealthier countries can’t afford any large-scale screening programmes with MRI.’

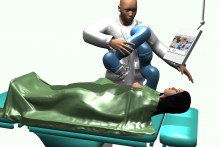

This is why the UT researchers are collaborating with parties such as Siemens, KUKA and universities in Verona and Vienna to build a robot that combines the best aspects of an MRI scan with cheaper and less precise technologies, such as an ultrasound sensor and a pressure sensor.

Muscle diseases

This will mean that patients need to spend just 15 to 20 minutes in the MRI scanner. ‘This produces an offline MRI image that you can combine, during the biopsy, with online images from the ultrasound sensor,’ says Farimani. ‘One of the biggest challenges in this project is to use the precise MRI image to locate suspicious tissue in the much more indistinct ultrasound image.’

In addition to breast cancer, Farimani and his colleagues are also focussing on biopsy for muscle diseases. But ultimately, he says, the technology should be suitable for all diagnoses where a small piece of human tissue needs to be removed from the body.

Collaboration with hospitals

Hospitals such as Radboud University Medical Center and the ZGT hospital group are also involved in the research project. The UT is working with these parties to bring the technology into line with market wishes. ‘The robotics in this project might actually be the simplest issue. Actually getting medical technology to market is often easier said than done,’ adds Farimani.

The MURAB project got underway quite recently. In November, MURAB received a Horizon2020 grant of 4.3 million euros. Some 1.2 million euros of this are going to the UT, which is managing the project. Besides Farimani, professors Stefano Stramigioli (project leader) and Ferdi van der Heijden are also responsible for project coordination; they are members of the CTIT research institute at the UT.