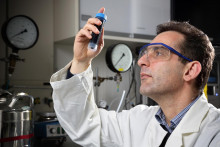

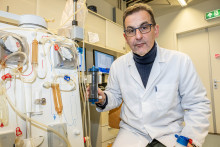

(Bio)artificial organs are the main research area of Professor Dimitrios Stamatialis, who is giving his inaugural lecture this week, on the 8th of June, 2017. ‘My main driver has always been to help patients,’ says the UT based scientist. ‘I was never in it to be “rich and famous”. I want to help through my research.’

In fact, the initial motivation to pursue a career in this field was very personal for Prof. Stamatialis: ‘My father’s had diabetes for twenty five years, which brought many issues. We all, as a family, had to adapt our lifestyle to help him through it. Even though the healthy diet was a welcome consequence for all, the continuous struggle to regulate my father’s diabetes with injections was always a great burden. I used to think “Wouldn’t it be fantastic to have a better solution, so my father wouldn’t have to take these injections?” And I knew that if I could do science, I’d like to focus on something that really helps others.’

Shortage of donor organs

After obtaining his PhD in physical chemistry at the University of Athens, Dimitrios Stamatialis started his academic career at the UT. He spent ten years at the Membrane Technology group before joining the Biomaterials Science and Technology group in 2011, where he’s now working on the development of (bio)artificial organs. “What are those?”, you might ask.

‘We are looking to engineer devices that mimic failing organs,’ explains the professor. ‘At the moment, people suffering from diabetes or failing kidneys require a donor organ, but there is a big shortage of those. For instance, the waiting list for a kidney transplant in the Netherlands is about four years. This means such patients have to go through dialysis and that people with diabetes need to rely on insulin pumps instead of getting a new pancreas.’

Artificial versus bioartificial

To offer better solutions to the patients, Prof. Stamatialis is working on artificial and bioartificial organs. ‘There is a big difference between the two,’ he points out. ‘Artificial organs can assist or mimic an organ and have no biological function. An example can be a new generation of an artificial kidney device that filters the person’s blood. Bioartificial organs contain actual biological cells and could potentially fully replace the failing organ. Bioartificial kidney devices use kidney cells, which could do complete blood filtration as a normal kidney. This offers a more complete treatment to the patients.’

Although bioartificial organs are the end goal, Prof. Stamatialis explains that we first need to develop good artificial organs, before we can add the ‘bio’ component to them. Which is why, while some artificial organs are already used in practice, bioartificial devices have a long way to go before they reach real patients. ‘It will be a long process, but the need for bioartificial organs is certainly there,’ says Stamatialis. ‘Our aging population will require such devices, because we can’t rely only on donors, not to mention that some organs – such as liver or lungs – are very hard to replace, but could be supported by an engineered device.’

‘We need all players on board’

What do we need to do to bring a bioartificial kidney or a pancreas to clinical practice? ‘We need all players on board – many research disciplines within academia, the government and also industry,’ thinks Prof. Stamatialis.

‘Government should listen to the needs of the society and support research projects that can help patients and that are affordable. Dialysis now costs about € 70,000 – 90,000 per patient per year. A smaller system for home use could significantly reduce these costs,’ explains the scientist. ‘The support of the private sector, especially of the large (pharmaceutical and other) companies should also be increased. Some of them are quite conservative and often focus on short term profits rather than supporting long term innovation projects. My big hope and wish is that some of the organs we have been working on could reach patients in my lifetime.’