While at the salon for a trim, Sarthak Misra discovered that his hairdresser knows exactly what he is up to. ‘I had been on television to talk about my research. My hairdresser told me she had seen the interview and thought my research was very interesting. I was quite surprised at that. I sometimes forget that my work is not only of interest to myself and my colleagues, but also to regular people.’

His area of expertise is not particularly difficult to explain: when we meet for drinks, Sarthak Misra has an answer ready to go. ‘Whenever people ask me what I do, I tell them I design robots that go into your body.’ That brings to mind terrifying visions of robots the size of spiders crawling into our bodies through our ears. In reality, the professor of Surgical Robotics from Twente works with microrobots the size of, say, sperm cells. They can travel to any point in our body via our bloodstream.

The example of the sperm cell was not chosen randomly; Misra's department garnered attention from all over the world with their microrobots that look like spermatozoa. With their long, flexible tails, they make swimming motions when exposed to a magnetic field. With this magnetic field, the microrobots can be wirelessly directed to where they need to go; think of e.g. an organ that needs medication or a blood vessel in the heart where a stent must be placed. The department also developed a kind of gripper robots in the shape of tiny starfish. Once they have reached their destination inside a patient's body, they can grab a tiny sample of the tissue that a physician wants to study. Such biopsies are usually performed with the help of a needle, which can be difficult if the tissue in question is located deep within the body. The wirelessly controllable microrobots can reach any organ without a doctor first having to cut into the surrounding tissue. With this technology, medical procedures are less invasive, more accurate and faster.

Few people object to research that is designed to make medical procedures more accurate and less bloody. Misra is therefore not afraid of negative reactions when he talks about his work. ‘The amount of social appreciation for my research makes the work very rewarding. People tend to be surprised that these things are actually happening and that they are no longer merely science fiction.’

In some cases, however, people's appreciation can lead to overly lofty expectations for the research. After a TV or radio performance, people often try to get in touch with the professor. ‘I get emails from people who suffer from a condition or know someone who does. They ask me if they can schedule an appointment with their doctor to see if the treatment might be right for them. I try to explain as carefully and clearly as possible that I am not a physician and that the technology is not yet ready for practical application.’

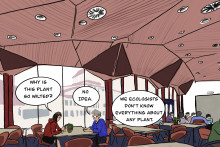

A common misconception, born in part out of the same lofty expectations, is that Misra's robots will soon make human surgeons obsolete. ‘In films, you sometimes see robots performing an operation autonomously. That is never going to happen; there will always be a human physician to make the important medical decisions.’