‘Do you want a cookie? A friend of mine brought them for me from China yesterday.' Xin Ming opens a large box of pastel-coloured cookies, individually wrapped in a thick layer of plastic and wax paper. Dryly: 'The Chinese love lavish packaging, out of a traditional penchant for politeness and a modern pursuit of ultimate hygiene.'

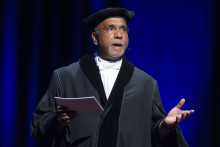

Ming came to the Netherlands in 2014 'for love'. In 2018, he obtained a master's degree in Philosophy of Science, Technology and Society in Twente. Since 2020, he has been working on his PhD research, which bears the working title Interdisciplinarity in Action. He interviews lecturers, students and policymakers from engineering programmes and analyses how they work together from different disciplines. ‘But don't ask me to summarize this in three sentences,’ he laughs, handing over a cup of tea. 'Interdisciplinarity is a bit of a hype, but if you ask people what they mean by it, and why they think it's important, you get very different answers. Social processes and cultural backgrounds play a major role.'

International in Twente

Politicians are calling for a reduction in the number of international students and English-language education at universities. But how does it really feel to leave your home country for a study or academic career in the Netherlands? In this triptych, journalist Minou op den Velde talks extensively with internationals at the University of Twente, about their backgrounds, dreams and cultural differences on campus.

Today part 1: PhD candidate Xin Ming from China.

The Apeldoorn mansion that Ming shares with his Dutch husband is a cheerful potpourri of brightly coloured furniture, large plants, ceramics he collects at flea markets and figurative art. The living room overlooks the water. Bees and butterflies dance around a white gazebo in the garden. If you would have told Ming as a kid how he lives now, he would have never believed it. He grew up as an only child in a village in Harbin, a metropolis in northeast China. Father worked for the government, mother taught Chinese at a secondary school. 'Our house was a kind of hut, in a ghetto of self-built houses. We had no fridge, no television and no telephone. Now I would call it poverty, but at the time most Chinese were poor, so it wasn't such a problem.'

The role of analyst and observer that Ming cherishes as a researcher fell to him at an early age. ‘My mother was bipolar. In her manic episodes, she seemed possessed. I remember being woken up at night as a seven-year-old boy because she had disappeared. My father found her at the train station, she had bought a ticket and wanted to leave us. The fear I felt at that time shaped me. My parents only had to come home a little later than agreed, or I panicked.'

How did you spend your days?

"My grandmother taught me to read Chinese characters when I was about two years old. Usually I drew on the walls and the table, that was just allowed. I had nothing else to do. The days at school were a grind. With seventy children, we were tightly packed in a small dark room, cramming boring facts into our heads. At home, life revolved around sickness and madness. Because of all those problems, I became more introverted, more isolated. When other children were playing outside in the sun, I would sit inside in the shade and watch, with the door open. I thought people were wondrous creatures, I just had no idea how to deal with them.'

Around the age of twelve, Ming realizes that he is attracted to men. It increases his isolation. ‘I didn't know people who were gay, you didn't see anything about it on television. It was like in the U.S. military: 'don't ask, don't tell.' I learned to hide my sexual orientation. Only with close friends could I share my feelings. I was lucky that I was never bullied violently, because with my small stature and girlish behaviour, I was perfect bullying material.'

‘It wasn't until I got a boyfriend when I was eighteen that I told my parents’

Did your parents know you were attracted to men?

‘No, you didn't talk to your parents about your feelings, and certainly not about homosexuality. It wasn't until I got a boyfriend when I was eighteen that I told them. My mother saw it coming a long time ago and supported me, but my father didn't like it at all. His message was: if people know this, you're going to be in trouble, and so is the family. People will look down on you and treat you badly. He said: 'It's better to be single all your life than to be in a relationship with a man.'

Ming's confession results in 'a day full of arguments and crying', but then the atmosphere at home clears up again. ‘I went on vacation with my boyfriend, but I lied to my dad that I was going with classmates. I don't think he believed me, because he said, 'Are you careful, boy?' At that time, people thought: if you're gay, you'll get AIDS and die. Sometimes I saw people who were gay marrying someone of the opposite sex in order to conform to social norms. But I didn't want to live a fake life.'

Shortly after his coming-out, Ming left for Beijing, 1,500 kilometres from home, to study philosophy. Together with five other students, he is assigned a dormitory of 15m2. Along the walls are four bunk beds, one of which serves as luggage storage. A small table is crammed between the beds. ‘You could barely walk there,’ Ming chuckles. ‘It was a happy time. Near the university there was a film archive that showed arthouse films, and I visited a lot of museums – everything was new. The economic tide was favourable, and a less conservative wind was blowing through the country. The 2008 Olympics had just ended. Everyone hoped for a future in which China would not be isolated, but would be part of the world.’

'Your life is a novel that you are going to write yourself'

To what extent was your choice to study philosophy related to your background?

Xin jumps up. 'Nice question! Because of my mother's illness, and my homosexuality, I was fascinated by the workings of the brain. But studying psychology was not an option with my curriculum. Near my secondary school there was a library where I often sat and read philosophy books. One of the first sentences I read was: 'Your life is a novel that you are going to write yourself.' And: 'Without evil, good has no meaning.' Later I discovered that these statements came from existentialism, but as a teenager I mainly thought: this will help me for the rest of my life! I don't have to be limited by my circumstances, I can live the way I want to.'

In 2013, Ming completes his bachelor's degree in philosophy with a thesis on free will. 'I wanted to know: if all particles follow a predetermined trajectory based on the laws of physics, how free are we as humans? And if we have a soul, how does it relate to our body? That question arose from the fact that my father turned out to have cancer, and according to his doctors, only had a short time to live. I wanted so badly to believe that he would live on somewhere as a ghost or as a soul.’

Ming wants to study Philosophy of Mind in America, a field that explores the connection between body, mind and consciousness. He returns to the family home to prepare for the application and to be able to spend time with his family. Then, his mother is forcibly admitted to a psychiatric hospital. 'I sank back into the swamp of all the problems at home', Ming recalls. But then something happens that changes everything: he falls in love. Online, he gets to know Menno de Jong, who is a professor of communication science in Twente and is temporarily working in Beijing. De Jong is 49 at the time, Ming is 21. But it works. ‘As a child, I never felt so comfortable with boys my age. I discovered that I was attracted to intelligent, mature men. Smart is the new sexy, isn't it?' After De Jong returned to the Netherlands, they video called every evening for a year. ‘While my parents were sleeping in the next room, I told him how scared I was for life. Slowly the thought arose that everything could be different if we were together. In the summer we were together for two months and in the winter I introduced him to my parents. My father said: 'I don't get it, but I'll have to accept it.' That's the coolest sentence he's ever said. I suspect that, with the end in sight, he thought: it's better to choose for your happiness than to trying to live up to society's expectations.'

'Deep in my heart I still have doubts'

The couple marries in the summer of 2014, and in September Ming flies to the Netherlands to settle here. 'It was a difficult choice. I thought: if I choose love, I'll give up all ambitions in Philosophy of Mind, and I'll leave my parents behind. Fortunately, my aunt was able to take care of my parents, but deep in my heart I still have doubts. I know I would have broken down if I had stayed at home. But in China, it is traditional for different generations to live together. Am I a bad person for depriving my mother of that opportunity?’

With a smile: 'When I left, something happened that encouraged me. When I checked in my luggage at Beijing airport, the man behind the desk asked: 'Are you going to study in the Netherlands?’ I said no, I'm moving for my relationship. Oh he said, 'Do you have a girl there?' I blurted out, ‘No, with a man!’ He looked a little surprised and then said, ‘How cool of you to do that, I admire you.’ That's how I came out to a Chinese airport employee.'

Xin Ming and Menno de Jong.

What did you know about the Netherlands?

'Not much, except that the Netherlands has a nice name in Chinese: hélán - literally it means lotus and orchid. But it sounds like Holland, not the Netherlands.'

How beautiful was the reality?

'The silence, I had to get used to that. I missed the liveliness of the streets, the morning market and the night market, and street food.'

'The threshold for integration is high'

How would you describe life here?

'Organised. In the Netherlands you have terraces, but they belong to a restaurant and close at a certain time. In China, you often play badminton outside. For a small fee, you can rent an entire field in a sports hall, but here you first have to join a club and get to know everyone. The threshold for integration is high.'

Six months after his arrival in Enschede, Ming starts his master's degree in Philosophy of Science, Technology and Society and takes the Dutch state exam. He doesn't immediately settle on campus. 'The international students and the Dutch students sat separately in class. Because I spoke some Dutch, I was sometimes admitted to a Dutch group, but I couldn't follow the whole conversation. That's the first thing I realized when I started learning the language: the context matters. You may know all the words, but if a certain term or television show doesn't mean anything to you, you're still an outsider. At the same time, I also feel like an outsider among international students, because they often share a Western background. Western music didn't emerge in China until later, so pop classics like ABBA don't mean anything to me, even though most international students sing along to those songs.'

The non-verbal communication also takes some getting used to. 'I remember we were talking about Lord of the Rings with fellow students. I told him that I had never seen the movies before, to which a Dutch boy said: 'Me neither!' He high-fived me, but I had no idea what that meant, so I kept holding his hand in the air for a while. He laughed, ‘Don't you know what a high five is?’ Oh, I felt so uncomfortable. I thought: there is so much I don't know, how can I ever function here? Someone once made a gesture with crooked fingers. Those turned out to be quotation marks. It meant something like ‘not real’ or ‘so-called.’ When I started my PhD research, there was a colleague who made a finger-crossed gesture. Like: ‘let's hope your research goes the way you hope.' He sighs softly. 'I still find those kinds of things complicated.'

Do you ever have to deal with discrimination?

‘When I came here, most of the people were friendly, but I remember running into two kids on the bike who started shouting 'Hey Chinese!'. That didn't feel good, but I don't know if that was really meant to be discriminatory. When I was sent my Chinese passport and had to pick it up at a pick-up point, the desk clerk said: 'Oh, did you get a Dutch passport? Congratulations!' I found it strange that people apparently assume that a Dutch passport is something to celebrate, as if it were a step forward. As if a Dutch passport is superior to a Chinese passport.'

Perhaps a factor is that China is seen here as an unfree country, where the government oppresses its citizens. Have you experienced it the same way?

'Not really. Until I left for the Netherlands, in 2014, I had the feeling that more was possible. Until 2007 we didn't have a computer at home. When I was sixteen, we suddenly got a PC and in a few years there was the internet, and social media platforms such as Weibo – the Chinese version of Twitter – and Renren – a kind of Facebook – emerged. My world became much bigger. People freely expressed their opinions and talked about all kinds of things. In 2013, Xi Jinping became president. In retrospect, you can see that during the change of power, a major change occurred in China. I can't pinpoint exactly what that change was, but with the arrival of a new ruler, a lot of things shifted culturally and ethically. After 2014, there was more and more censorship.'

Do you mean you don't want to say that it was because of the new government?

‘Oh no. The government played a role in that, but it was a complex social dynamic. The censorship started at the time of the change of power, but you won't hear me say that there is a causal relationship.'

Is it dangerous for you to make such a claim?

‘Well, I don't want any hassle. Because I'm not anonymous in this interview, am I?'

That's correct. How would you describe the change?

'Around 2011, many social problems became visible through social media. People felt that the internet could change their lives. That if they would make their voices heard loud enough, poverty or abuse of power would come to an end. At a certain point, we noticed that if you saw a post on Weibo that had received thousands of comments, and you clicked on it, suddenly there was not a single comment or only a handful of similar reactions, which were quite different in content from your own intuitive response to such a post. Later, you had to identify yourself with an ID card to be able to use websites, which meant that you could no longer be anonymous online.'

In May 2024, Amnesty International published a study in which Chinese students stated that they are being watched and harassed by Chinese authorities and fellow students at Western universities. Nearly a third of them said that family members in China had been threatened by authorities to prevent students abroad from criticizing the Chinese government. Ming also watches his words, he says when asked. 'A Chinese friend recently urged me not to just give my opinion about politics or the current government to Chinese people here.'

'I know that a lot of Chinese students here mainly move in Chinese circles'

How big is this problem for Chinese students in Enschede?

'I have Dutch friends myself, but I know that many Chinese students here mainly move in Chinese circles, which makes it easier for the things they say to be picked up by compatriots who play a role in the Chinese government. Recently, it was announced that the Chinese government has opened two police stations in Rotterdam and Amsterdam, supposedly to help Chinese citizens with passports and business issues. But there is a serious suspicion that they were set up to supervise Chinese in the Netherlands. I take these kinds of things into account, so I can't honestly say what I think about Chinese society or the government to people I don't know well.'

You don't dare?

'No, not even in an interview. Some students are braver than I am, and others prefer to remain silent, because it benefits them. In an intellectual environment like a university, you would expect people to be more critical and involved in social issues. But that is certainly not the case at our university, the attitude is mainly pragmatic. Many Chinese students in Twente are more interested in making money and acquiring patents than in social change. As long as they are doing well financially, they are fine with everything. I think a lot of Chinese students come to the Netherlands because they've heard that everything here is clean and that everyone can afford luxuries. As soon as they discover that the average Dutch person is not super rich, they are disappointed, which translates into a certain kind of nationalism towards China.'

'The wealth gap and class differences are increasing, which disappoints me'

What were your expectations about the Netherlands at the time?

‘Before I came here, I thought Europeans were more socialist than we were in China. Because in my youth, China changed from a socialist state where people were equal, to a capitalist country with a huge poverty gap. I see the same dynamic in the Netherlands. The wealth gap and class differences are increasing, which disappoints me. On campus, most students are wealthy. The other day, a Dutch bachelor’s student casually told me that his parents had just bought a castle in France. That's a strange sensation, because in China it's traditionally mainly young people from poor families who go to university, in order to change their lives through knowledge.'

You started your PhD research in 2020. How does your current life differ from that of a PhD student in China?

'As a PhD candidate, you are given a lot of space here, whereas in China you are often employed by your supervisor. Even in your free time, you are expected to be available, even when it comes to your private life. I once heard a professor instruct her master's students to do her daughter's homework. Another professor demanded that his students help him with his move. In China, it's normal to work overtime, which is related to the hierarchical culture.'

Do you feel that you have more freedom to do research here?

'I think so. I don't think I would get permission in China to investigate what people think about the current government of Xi Jinping, but in the Netherlands I could easily investigate why many people are dissatisfied with 13 years of VVD policy. On the other hand, university research here is highly dependent on funding from the government and industry, which makes it easier to fund a certain type of research here.'

What kind of research do you think is less likely to be funded here?

'Research that cannot easily be translated into a practical tool for the market. The research system may be free from political or legal interference, but it is not free from the social context, in which business dominates. It is not for nothing that there is now a lot of discussion about the University of Twente's collaboration with the fossil fuel industry.'

'I have the feeling that many internationals see their life in the Netherlands as a step on the career ladder'

You've been in the Netherlands for ten years now. To what extent do you feel at home?

'I feel part of Dutch culture, but I will always be an outsider.' Ming bursts out laughing. ‘There are things I never want to learn, like eating bread! I'm still a rice person. On the other hand, I've been here for so long that I feel very different from many young scientists who come here for a while. I have the feeling that many internationals see their life in the Netherlands as a step on the career ladder, so they don't feel the need to integrate. I think it would be a good idea for international students in the Netherlands to reflect on their position in society. Is this just a stopover in your life, for which you bear no responsibility, or do you also want to contribute something to Dutch society? Internationals have a strong opinion about reducing international education, because oh, how bad the Netherlands is, the policy is no good at all! But why do so many people vote for politicians who don't want international students? Could it be that the universities or the intellectuals themselves have done something wrong? I think the answer lies in the social divide, the attitude, the social bubbles. You can claim that you are not treated well as an international, and you can complain that no one wants to speak English with you, but the interest has to come from both sides.'

What did you do to integrate?

'I worked at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen for a while, where I spoke Dutch every day. The fact that I have Dutch friends is also because I got to know the Dutch culture and humour.'

Is Dutch humour different from Chinese humour?

'Oh yes, huge. I remember watching the comedy series Jiskefet for the first time, I found it so uncomfortable! I didn't understand why people thought that was funny. I now love that Dutch irony. I still can't stand embarrassing scenes, but I love all that sour stuff, complaining, and sarcasm. You don't see that in Chinese comedy. The Chinese especially like puns, they laugh when two words sound a bit the same.'

Ming hopes to obtain his PhD in 2025. He has not yet mapped out his professional future, but he dreams of research that merges his interest in philosophy and sociology. 'I want to investigate how people feel today, why that is the case, and what that means for society.'

When his husband retires in a few years, he would prefer to live somewhere in Asia for part of the year. 'Because I think the Dutch winters are long, dark and rainy.' But a permanent return to his homeland is not in the cards. 'Life in China is only fun if you have a lot of money and don't have to work 24-7 for a boss. I wouldn't be able to live as freely in China as I do here, because the government doesn't value homosexuality. Homosexual storylines continue to be removed from movies and television shows. I wouldn't be able to walk hand in hand with my husband in broad daylight. Sometimes I think: maybe that's why I got married? Marriage is quite an old-fashioned institution, but to me it feels cool, because it's not allowed in China.'

ABOUT XIN MING (Harbin, China, January 4 1991)

2009 – 2013 Bachelor of Philosophy, Beijing Normal University

2015 – 2018 Master Philosophy of Science, Technology and Society, University of Twente

2016 – 2018 Teaching Assistant, Twente University

2019 – Digital Audience Guidance Officer, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

2020 – present PhD research Interdisciplinary Engineering Education, University of Twente