When Ben Betlem started studying chemical engineering at the THT in August 1970, he was part of the first intake which did not have classes on Saturdays. 420 students – 12 of them women – arrived at the campus gates that year. All of them were budding engineers coming to begin their studies and to find their place in the homogenous community already on campus. However, though the campus community was relatively closed off from the outside world, it wasn’t immune to developments taking place beyond its walls.

It was the seventies, after all - Labour (PvdA) versus the VVD, the Vietnam war, the oil crisis, peace signs and countless protests, flowing hair, flares and flower power. During his introduction, Betlem ended up in an ‘alternative flat’ on Calslaan. ‘It was a real hippie floor. A lot of the people who lived there came back from the first days-long pop festival in the Netherlands in Kralingse Bos. They’d all taken friends with them. It was a real culture shock, especially as I’d not long left boarding school,’ says Betlem. Though he never became a hippie himself, he still listens to the musicians of then today – some that even used to play in the Vrijhof at the time, or outdoors on campus.

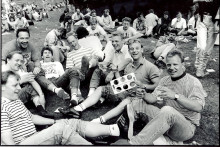

Introduction of new employees in 1971.

Early ideals fading

In the early ‘70s, the THT was in the throes of adolescence. Betlem remembers that many of the ideals from the early days came under pressure or disappeared. ‘It was a tumultuous time. My studies were still based on those early ideals: a foundation year for all students, then a three-and-a-half-year baccalaureate. After that, if you didn’t move straight into industry, you had a two-year master’s course, which at the time was called the doctoraalexamen. Throughout all of that, as a chemistry student I took nine social science courses.’ From up close, Betlem saw more and more things begin to crumble. ‘Students stopped being required to live on campus, fewer social sciences were offered, the baccalaureate never really took off, questions were raised about the foundation year which was later abolished. The THT was increasingly becoming a two-core institution, one core being technology and the other social sciences.’

'Back then only just over four hundred new students arrived each year'

Management was being restructured too, with an interim university council (Hogeschoolraad) even before the University Administration (Reform) Act came into force in 1972. The council, to which Betlem was elected in 1976, had quite the influence. ‘Twente was the first university in the Netherlands to have electoral associations that extended through all parts of the academic community. The University Council was like a parliament.’ The THT’s finances were a touchy subject, he says, mainly due to the low intake of students. ‘Back then only just over four hundred new students arrived each year – something that’s unimaginable nowadays. The lowest intake was around two hundred and fifty, following the Secondary Education Act. Parliamentary questions about the continued existence of the THT were being tabled as late as 1974.’

Building occupation

Sometimes internal bombshells went off. One such occasion was the occupation of the Business Administration building (now the Spiegel) in August 1972. This was done in protest against the decision to exclude students who refused to pay the increased tuition fees, which had gone from 200 to 1000 gulden. Some fifty students occupied the building, including members of the Progressive Coalition Electoral Association, which sat in the University Council, and the Marxist-Leninist Student Collective. ‘That occupation just goes to show you can’t keep the zeitgeist away, however closed the campus community might be,’ says Betlem. ‘Of course, this was also very immediate as the fee increase hit students in the pocket. The THT was a younger and less hierarchical institution than others, so political engagement wasn’t as fierce as at other universities in the country, but that’s not to say there was none. Students at the THT were on the left and far left much more than they are today. There was a real thirst for creating an egalitarian society.’

'Students vehemently opposed big industries and imperialism'

The occupation of the BB building in 1972.

This was reflected in the University Council, which for instance objected to contract research for military purposes in 1972. Two year later the Council held that the campus should be a reception centre for students and employees who had fled from countries where human rights were being abused. The politics also made their way to the lecture halls, especially in the social sciences, remembers Betlem. ‘There was a lot of discussion about nuclear weapons during Philosophy of Science and Technology. In sociology of business, you couldn’t avoid the Yugoslav model of workers’ self-management being glorified. Students were letting themselves be heard loud and clear, and vehemently opposed big industries and imperialism. In International Law, a student at the back of the lecture hall once stood up and gave an impassioned speech against imperialism. The lecturer, who was just trying to explain a point, burst into tears. That’s always stuck with me.’

'I knew academic staff members who had only one publication to their name'

Nooks and crannies

Highly charged moments like these contrast sharply with how Betlem remembers his student days on the whole: pleasant and amiable. The small, closed campus community was fertile terrain for this kind of atmosphere to develop. ‘There was hardly any pressure on students, financially or otherwise, except military service if your studies went on for too long. That said, there were plenty of eternal students around. The labour market wasn’t brilliant and you were primarily responsible for yourself,’ he says. The culture was different for academic staff, too. ‘I’d guess that a great many professors didn’t have a PhD - at the time, professors were still required to have experience in industry. There wasn’t much pressure to publish. Knowledge application was far more important. I knew academic staff members who had only one publication to their name – and it was just from a conference.’

Second from the left: Ben Betlem.

It was also easier to forge a personal bond. Just like other students, Betlem regularly met with staff from the graduation group. He was occasionally invited over for dinner or helped out with odd jobs or moving house. He regularly played billiards with his graduation supervisor in the Bastille, a special place for Betlem. ‘Unfortunately, all of those lovely little nooks and crannies have disappeared. That’s where the mensa was, too. There was even a bowling alley and a chip stand, which I visited regularly.’

Ben Betlem nowadays

Ben Betlem studied chemical engineering at the THT from 1970 - 1977. He then went on to work as a research assistant at TU Eindhoven and worked at Koninklijke Hoogovens (now Tata Steel), among other places. He returned to UT in 1988 and obtained his doctorate in the 90s. In 2007 he became programme director for the bachelor and master’s courses in chemical engineering and masters in nanotechnology. He retired in March 2021.

Community

In any case, teaching, research and community life were all on much more of an even footing back then. ‘Sport was a much bigger part of life on campus,’ says Betlem, who was on the Kronos board for four years. ‘You could train five times a week – though I never went to a morning training session. Afternoon training sessions coincided with tutorials, though, so you had to make sure you were in the right tutorial group.’ As the sports associations didn’t have many potential members on campus, some of them looked for members elsewhere. ‘The tennis and badminton clubs, for example. They deviated not only from the Drienerlose green and black colour scheme that all of the clubs wore back then, because of the sport-specific rules, but as mixed sports they also struggled with recruiting enough women as members. That worked out well, though, as I met my wife on campus. She was an external member of the DIOK badminton association.’

'It’s not by chance that buildings here aren’t named after a faculty'

It’s hard to compare the way things are these days to how they were then. Betlem knows that all too well - earlier this month, he retired and left the UT after almost 35 years. Was the grass greener in the seventies? ‘Maybe a little. What I can say is that I remember my student days very fondly. The typical Twente multidisciplinary approach always appealed to me, and since the Twente Educational Model was introduced in the last few years it’s made a bit of a comeback. It’s also not by chance that buildings here aren’t named after a faculty. The disciplines here are woven through one another, which strengthens our sense of community. This is something the university should foster, now and in the future.’

Ice skating on the pond at the main entrance, in 1975.