No flags or balloons in Bram Nauta’s office on the second floor of Carré. But what does catch the eye is a row of mobile phones - from an old-fashioned Nokia to a modern smartphone - and behind it, a glass plate with a circuit depicted in LED light. Or rather: the circuit. It is a gift from his colleagues at Integrated Circuit Design in honour of the Stevin Prize.

Brainwave at the swimming pool

Before long, the university professor launches into a concise lecture on the now world-famous Nauta circuit, which formed the basis for technologies such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth and can still be found in many people’s pockets today. ‘The circuit has stood the test of time,’ says Nauta. ‘In the end, it’s actually quite a straightforward system: two inputs on the left, two outputs on the right, and four inverters in between. Each wire connects to an input or output. In a circuit, you ideally want to see two things: lots of amplification and lots of speed. Whereas a regular circuit can quickly start malfunctioning, this thing can handle it all. Through its practicality and efficient performance, it offers the best of both worlds.’

'I didn’t discover any new material or a black hole. I'm just tinkering'

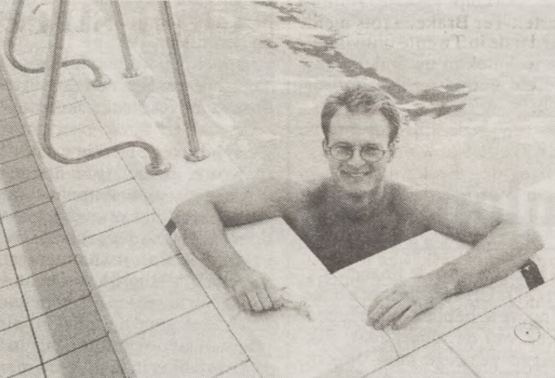

Much has been said and written about the eureka moment that eventually led to the renowned circuit, all the more so since the announcement that Nauta is one of this year’s Stevin Prize winners. One day, Nauta hit a roadblock in his PhD research. He had mapped out a complex system with up to twenty inverters... He decided to go swimming in the indoor pool on campus and while swimming laps, he suddenly realised how to design a compact circuit out of that complex tangle. He did so on a piece of newspaper he borrowed from the pool manager. Speaking of newspapers, Nauta still remembers the headline for the article in UT Nieuws (the printed predecessor of U-Today). ‘Brainwave in swimming pool’ it read, which I thought was rather clever.’

On the left: Nauta about his finding (October 1991). On the right: Nauta about his eureka moment in U-Today's Science & Technology magazine(December 2017).

Tinkering

It turned out to be the first step towards an impressive list of achievements, the most recent addition being the Stevin Prize early this month. Nauta describes the recognition that comes with it as ‘nice’. ‘A bus full of people drove from Twente to The Hague for the award ceremony. Unfortunately, I was only allowed to invite 75 people. It is the joint highest scientific award you can win in the Netherlands (alongside the Spinoza Prize, Ed.), so it’s certainly something special. And it’s for applied research too; I didn’t discover any new material or a black hole. I’m basically just tinkering, an architect assembling something with existing building blocks.’

Handiness was ingrained in Nauta from an early age. Before he studied and obtained his PhD at the UT, he progressed from pre-vocational secondary education (MAVO, now VMBO) and senior general secondary education (HAVO) to pre-university education (VWO). As a matter of fact, after he had finished primary school, he was even advised to attend LTS, the lower technical school, for his continuing education. ‘I would also have been happy as a carpenter,’ says the professor. ‘When something is broken, I want to fix it. I remember creating a chain out of one solid block of wood, just by drilling and sawing. For my fifth birthday, my father gave me a block of wood and a thousand nails and he said: ‘turn it into a block of iron’. To this day, I hammer every nail perfectly straight.’

'Anywhere else, it would be unthinkable for someone to pass on a secured grant to a colleague'

Balancing act

The connection between carpentry and chip design is easy to make. ‘Working with your hands is working with your head. Chip design is precision work, you can't afford any mistakes. Designing a chip is like programming, with the main difference being that a mistake during programming can be solved in no time. If you make a mistake in chip design, you lose maybe a year’s work’, says Nauta. ‘So you have to be both precise and sufficiently creative and innovative if you want to be at the forefront of this field. That’s a very fine line to balance on.’

But there are multiple explanations for his recent success. It also has to do with the people around him. ‘Within the department, we have an unwritten rule that we don’t bother each other, but we do help each other if we can. In other departments, there are often multiple PIs (Principal Investigators, Ed.), who don’t collaborate. Anywhere else, it would be unthinkable for someone to pass on a secured grant to a colleague. Here, projects are handed over internally, out of collegiality.’ Finding the right people is a crucial element in this, says Nauta. ‘I’ve always been told I have a knack for that. You often see it in people’s faces, in the lecture hall too. Someone who doesn’t just stare blankly ahead and nod, but challenges you and asks questions. Someone who wants to understand.’

Indeed, 2023 is the year in which many things came together for the professor: Nauta celebrated the 25th anniversary of his Integrated Circuit Design department, he received the Dutch Innovation Award last May (‘a prize that was apparently created especially for me’), the ‘Dutch Nobel Prize’ in the form of the Stevin Prize... ‘And I also became a grandfather,’ he is quick to add. ‘Yes, it has been a good year.’

'It almost feels like I’m redundant, even though I’m still bursting with ideas'

Redundant

When asked what he will do with the 1.5-million-euro Stevin Prize, Nauta’s answer to de Volkskrant was: ‘Tinker’. ‘It’s not like I need to take on more PhD candidates to start a new project. I currently have 24 PhD positions open; the last one will start in five years’ time and when that person completes their PhD four years later, I will retire.’ He wants to use the money to invest in lab infrastructure and raise the profile of his field. And create some more space for research that does not necessarily need to lead to anything right away. ‘There are a few things - fundamental things - that I still don’t understand very well. I want to invest time in these, to understand them better. Even if it’s not very useful right now, it might be in ten years’ time.’

But at the same time, he is no longer required to do anything; Nauta has effectively secured more research money than he can spend. ‘It’s not like I wake up with the idea that I need to raise money. That stimulus is no longer there, I don’t have to do anything. On the one hand, that is a reassuring thought. It almost feels like I’m redundant, even though I’m still bursting with ideas. Besides: it’s time for the next generation to learn. I want to help them do that.’

ChipTech Twente

To top it all off, this year also saw the ‘explosion’ of ChipTech Twente, a collaboration of companies and scientists centred around Nauta’s department. The professor will be very busy with that too. Nauta envisions a modest role for himself within the cluster, but the plans are ambitious. ‘To have Twente as the hotspot in Europe in the field of chip design, that’s the goal. Everyone knows ASML as the centre of the semiconductor industry. Twente must become the epicentre for chip design.’

'I'd rather stay in a place where I can build something myself, than ride on the back of someone else’s success at Stanford'

One of his motivations is the love for the region in which the Hengelo native grew up. ‘That absolutely factors into it. There used to be just one small chip design company in Twente, called Bruco, which was located in Weerselo. Because of that, it wasn’t easy to retain talent. 25 years ago, this field was uncharted territory in Twente; now, nine companies specialising in chip design have established themselves within biking distance of UT. By developing the industry, you provide people with a reason to stay.’

Building something

The fact that an initiative like ChipTech Twente has now taken off is anything but a matter of course, according to Nauta. ‘Anne-Wil Lucas (former area director of Kennispark, Ed.) set the ball rolling when she noticed all this activity.’ Within the UT, Nauta never felt that ‘traction’. ‘We also tried to establish a chip cluster at UT, but it didn’t get off the ground. It was just one little department - albeit a good one - backed up by many companies. And in microelectronics at that, which, of course, is not exactly nano-electronics. The centre then shifted to MedTech... But it’s a good thing that UT has put chips on the agenda after all. I hope this will further strengthen the region and encourage more graduates to stay here.’

In a way, 2023 feels like the year in which Nauta has got his dues: success and recognition, in whatever form, despite forces that worked against it. And on his own merit too. ‘Sure, I've had offers from other universities. From Silicon Valley too. But I'd rather stay in a place where I can build something myself, than ride on the back of someone else’s success at Stanford.’