The ‘Technologies for Women’s Health’ pillar at the UT aims to develop technologies for prevention, diagnosis and treatment of diseases that (primarily) affect women. ‘We want to support and investigate women’s health throughout the life span,’ says professor Sabine Siesling, chair of the pillar. ‘Our research projects cover diseases specific to women, such as breast cancer and ovarian cancer, but also diseases that occur more often in women, such as osteoporosis. On top of that, we would like to understand why diseases manifest differently in women than men and approach healthcare from women’s perspective. Take cardiovascular diseases, for instance. If women get a heart attack, they often get nauseous but that is not considered one of the symptoms and they get improperly diagnosed.’

Women’s health has been underrepresented in medical investment, research and innovation, explains Siesling. ‘Men form the majority in medical trials, for example. This has led to solutions that do not adequately support women. While women have longer life expectancy than men, they will spend 6-7% longer of their life in ill health. Women experience higher complication rates. Female patients are 50-75% more likely to have an adverse reaction to medications than men. Women are also diagnosed several years later compared to men.’

More than two dozen UT scientists have therefore joint forces within the new pillar, working on a large variety of projects but all aiming to improve women’s health and wellbeing. ‘One of our goals – and the research line I work on – is to design new data strategies and technologies for and with women,’ says Siesling, who works as a clinical epidemiologist at the UT and at the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland). The main topic of her research is breast cancer. ‘I look at variations in care for patients in between different hospitals, and I try to determine the reasons for these variations and whether they influence the outcome – in terms of medical results, as well as the patient’s quality of life. I’d like to see if we can use this differences to find out which treatment is best suited and make predictions on outcomes to support more personalization of care.’

‘We want to support and investigate women’s health throughout the life span’

Taboo topics

Anique Bellos Grob, Assistant Professor in the Multi-Modality Medical Imaging group, is an expert in urogynaecology, which ‘essentially involves everything that can go wrong with female pelvic floor’. The focus of her research projects is pelvic organ prolapse (POP), a highly common but generally unknown issue which affects millions of women. Simply put, POP refers to a pelvic floor organ, such as bladder, uterus or bowel, protruding from the opening of the vagina. This leads to many problems, such as urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, pain during sexual intercourse and more.

‘All of these are taboo topics,’ says Grob. ‘Issues such as fecal incontinence is not something we generally talk about. At the same time, about 40% of all women over seventy years old suffer from one or more of these conditions. Pelvic organ prolapse is mainly caused my pregnancy and vaginal child birth, when the muscles need to stretch tremendously. When the women are young, the tissues recover and surrounding tissue gives support. After menopause, however, all our tissues weaken and that can lead to prolapse. Because it is taboo, women generally don’t visit the doctor but they experience a big decrease in quality of life. Just imagine all the things that you suddenly could not do if, let’s say, you suffered from fecal incontinence. If you worry that feaces might leak out, you will probably not often visit anyone, travel, go swimming or anything else.’

Limitations

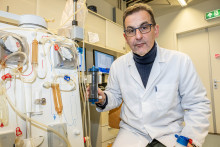

The diagnostics of POP are very limited at the moment. Medical specialists can only apply physical examination while the patient is lying down, but most women experience the biggest problems when standing up. That is why Grob is excited about doing research at the UT. ‘We are the only ones in the country with access to a tilting Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scanner, which allows us to examine the patients in an upright position. This can give us a lot of insight into the prolapse and possible treatment.’

POP can be treated, but – as with the diagnostics – only within limits, explains Grob. ‘I have my own outpatient clinic at the ZGT hospital. I tell all my patients that they basically have four options when it comes to treatment of the prolapse. The first option is to do nothing. The prolapse leads to a much lower quality of life, but it will not kill you. You may therefore choose to simply live with your symptoms. The second option is physiotherapy and muscle training. The third option is pessary – a silicon ring, which is placed in the vagina and physically supports it, so it doesn’t prolapse. This solution unfortunately only works in about 50% of the cases. The last option is surgery. It is not high risk, but the success rate is low. We have observed 30%-50% recurrence after only two years, meaning that in two years you have a high chance of being where you started.’

‘Because it is taboo, women generally don’t visit the doctor’

At the moment, we can’t make good estimates of when the treatments will or will not be successful. Grob’s research lines therefore focus on increasing the number of women who can be helped with treatments, especially the pessary, and decreasing the number of recurrences. ‘I’m using MRI and ultrasound imaging to find out what can be observed before and after the surgery. Are there some aspects that prevent the surgery to be a lasting success? With another study, we focus on understanding how the pessary actually works. We don’t really know how and why a pessary stays in place and how it helps with the symptoms. In all cases, the ring needs to be placed a bit differently and in some cases it works, in others it doesn’t. This relates to my third study, which is working towards tailor-made pessaries.’

Acquiring funding for this line of research can be tricky, admits the assistant professor. ‘It’s a taboo topic, people don’t tend to discuss prolapse or fecal incontinence. On top of that, it’s not a ‘life and death’ problem, it’s about increasing quality of life for many women,’ says Grob. ‘That is why I’m glad that the UT has a dedicated pillar for Women’s Health. Together we have a unique opportunity to focus on these topics. We are also discovering that many of our research topics might be related. For example, if you breastfeed, it might impact your pelvic floor recovery after labor. If we combine our work, maybe we can find more connections – and attract more funding.’

Helping women breastfeed

Breastfeeding is indeed one of the other topics researched within the Women’s Health pillar. Nienke Bosschaart, Associate Professor in Biomedical Photonic Imaging, has recently obtained an ERC Starting Grant to develop new methods to unravel lactation insufficiency and to help women breastfeed. ‘Breastfeeding offers a lot of health benefits for both mothers and babies, but it is also associated with many challenges,’ says the UT scientist. ‘At this point, we know surprisingly little about what happens during breastfeeding and what causes lactation problems. We just don’t have dedicated technologies for this topic.’

Women, specifically mother and child care, have always been at the centre of Bosschaart’s research. She has worked on a noninvasive alternative to blood sampling in babies and, in her second main research line, she focuses on human milk and lactation. In a nutshell, her field of expertise is biomedical optics and developing new technologies to support mothers and newborns. ‘Optical technologies have a lot of advantages,’ she explains. ‘They are noninvasive, harmless and give you a lot of information.’

‘We know surprisingly little about what happens during breastfeeding’

Bosschaart’s most recent project looks into lactation insufficiency. ‘I see this as a challenge that we really need to solve,’ she says. ‘Breastfeeding has many advantages. For mothers, it reduces the risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer. For babies, it boosts their healthy development. The WHO recommends that women exclusively breastfeed for the first six months, but only a minority manages to do that. From a social point of view, there is also a lot of pressure on women to breastfeed, but it is not only up to them. We need to support them much better.’

The most common reason why mothers stop breastfeeding is because they believe they don’t produce enough milk. ‘My project therefore has two goals,’ highlights Bosschaart. ‘Measuring how much infants drink and measuring what happens inside the breast - how its physiology regulates the milk supply. In both of these cases, I will use non-invasive optical tools.’

Working within the ‘Women’s Health’ theme is nothing new for any of these scientists, but they appreciate that the pillar was established at the UT. ‘We are building a consortium focused on this topic, so that we can make more progress in care for and with women,’ says professor Siesling. ‘Collaboration gives us more power to achieve our mission: to empower women through knowledge and innovation.’